Owen Collumb’s life changed forever in 1993 when, at just 21 years old, a motorcycle accident left him paralyzed from the waist down. Unable to move his legs and with only limited control over his arms, he faced immense challenges transitioning back into daily life. After years in assisted living, he fought for independence, eventually moving into his own Dublin apartment where he could live on his own terms.

Collumb didn’t just survive; he thrived. He took on multiple jobs supporting disability rights organizations and advocating for people facing similar barriers. This determined spirit led him to an unlikely stage: the Cybathlon. Held every four years in Switzerland, this unique competition pushes the boundaries of assistive technology by pitting teams against each other in a series of “everyday” challenges designed to simulate real-life tasks. Think wheelchair racing, object manipulation, and even virtual ball throws – all completed using cutting-edge prosthetics and brain-computer interfaces (BCIs).

The Cybathlon isn’t about showcasing technological marvels; it’s about celebrating human resilience and potential. As one of the competition’s founders, Roland Sigrist, puts it, “They’re the masters of the technology, and not the other way around.”

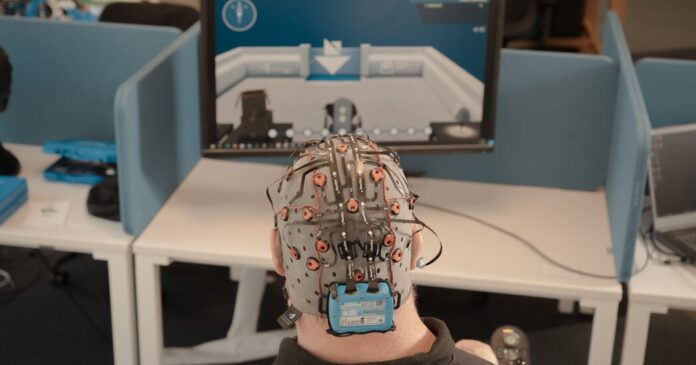

For Collumb, who has participated since the inaugural event in 2016, the heart of the Cybathlon lies in its most abstract category: BCIs. These remarkable devices allow individuals like him to control computers with their thoughts alone, transforming a mental image into actionable command. Imagine willing a cursor on your screen to move – that’s essentially how BCIs work. For someone paralyzed from the neck down, this technology offers a lifeline to independence. It could mean controlling a wheelchair, playing video games, or simply browsing the internet – all through the power of their mind.

The Cybathlon serves as a powerful microcosm of our rapidly evolving relationship with technology. As artificial intelligence accelerates progress in areas like robotics and bioengineering, the lines between human and machine are becoming increasingly blurred. The questions these advancements raise are profound: How much should we embrace this integration? Will it ultimately improve lives, or create unforeseen challenges?

Collumb’s story offers a compelling glimpse into one possible future. It underscores that technological innovation is most meaningful when it empowers individuals to overcome limitations and live fuller lives on their own terms. He embodies the Cybathlon’s spirit: “This isn’t showing your disabilities, it’s showing what you can do,” he says. “You may be in a wheelchair, you may not be able to move, but you can compete.”