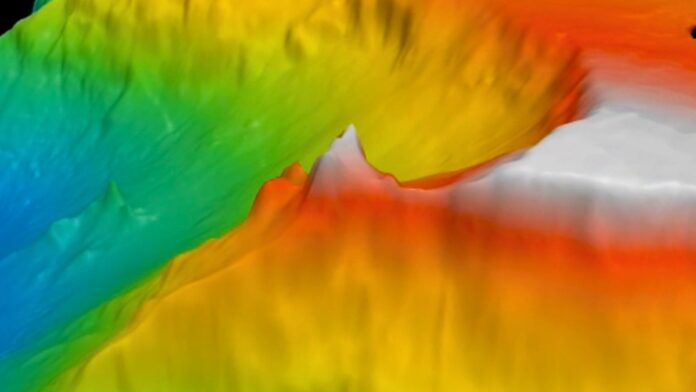

A unique geological formation, dubbed the Lost City, lies hidden over 700 meters beneath the ocean surface near the Mid-Atlantic Ridge. Discovered in 2000, this hydrothermal field is unlike any other known on Earth: a landscape of towering carbonate structures, some reaching up to 60 meters in height, rising from the dark ocean floor.

A World Without Sunlight

The Lost City doesn’t rely on volcanic heat like most deep-sea vents. Instead, it’s powered by chemical reactions between seawater and the Earth’s mantle, releasing hydrogen, methane, and other gases. This process sustains a thriving, oxygen-independent microbial ecosystem, feeding snails, crustaceans, and even larger animals such as crabs and eels. This ecosystem is particularly significant because it doesn’t depend on atmospheric carbon or sunlight—suggesting that life could emerge in similarly harsh environments elsewhere in the solar system.

Ancient Origins, Modern Threats

Researchers believe the Lost City has been continuously active for at least 120,000 years, potentially much longer. A recent core sample of mantle rock, over 1,268 meters long, recovered from the field, may hold clues about the origins of life on Earth. The structure of the Lost City itself—massive calcite chimneys—suggests long-term stability, unlike more volatile volcanic vents.

However, this unique habitat is now under threat. In 2018, Poland secured mining rights in the surrounding deep-sea area. While the thermal field itself is not rich in mineable resources, disruption from mining plumes could devastate the surrounding ecosystem. Scientists argue for its protection as a World Heritage site before irreversible damage occurs.

The Lost City stands as a rare example of an ecosystem that may exist on other ocean worlds such as Europa and Enceladus, or even on Mars in the past. Its survival depends on safeguarding it from human interference.

The Lost City is not just a geological curiosity; it’s a living laboratory and a reminder of the potential for life to flourish in the most unexpected places. Protecting it is not just about preserving a natural wonder, but about understanding the origins of life itself.