A new study confirms that specific bacteria, rather than yeast, are the primary cause of auto-brewery syndrome (ABS) – a condition where individuals become intoxicated from their own gut fermentation, even without consuming alcohol. This research, the largest of its kind, clarifies a long-standing medical mystery and may point toward future treatments.

The Science Behind Internal Intoxication

Researchers analyzed stool samples from 22 diagnosed ABS patients, comparing them to household members without the condition. They found significantly higher levels of two bacterial species in those with ABS, confirming earlier suspicions. This isn’t a fringe phenomenon; while rare, these patients undergo rigorous testing to prove their bodies literally brew alcohol internally.

The problem is that ABS is often misdiagnosed. Patients are frequently dismissed as secret drinkers, leaving them without the medical attention they need. Untreated, ABS can lead to liver damage, social problems, and even legal troubles.

Bacterial Culprits Identified

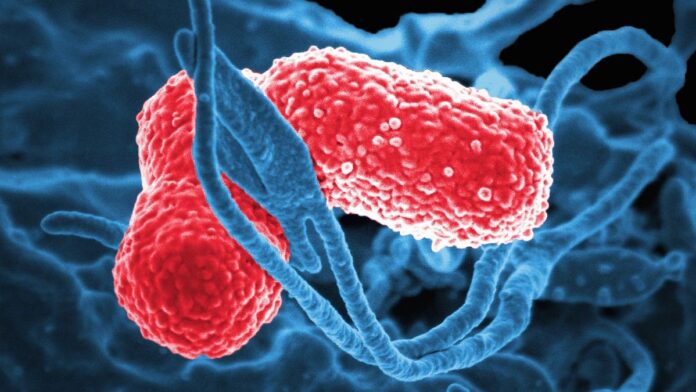

The study pinpointed Klebsiella pneumoniae and Escherichia coli as key ethanol producers in ABS patients. Importantly, the amount of ethanol produced by gut bacteria directly correlated with measured blood alcohol levels. During periods of remission, these bacterial strains were less prevalent.

One patient experienced over 16 months of sustained remission after receiving a fecal transplant from a healthy donor. This dramatic improvement underscores the gut microbiome’s critical role in ABS. The donor transplant reset his gut microbiota, essentially curing him.

Potential Treatments and Broader Implications

Researchers suggest several avenues for relief: dietary adjustments, probiotics, or even engineered stool transplants to promote ethanol-metabolizing bacteria. Although some cases may involve yeast, this study reinforces the bacterial link.

The implications extend beyond ABS. The study highlights how imbalances in gut bacteria can impact human health. Given that low-level ethanol production has been linked to conditions like diabetes and fatty liver disease (the most common liver ailment worldwide), scientists are now questioning how widespread this phenomenon may be.

“Our study underscores the importance of the gut microbiome and microbial metabolites to human health.”

The study raises a fundamental question: how often does microbial ethanol production occur in the general population, and what are the broader pathological consequences? The answer may require a wider look at how gut bacteria influence our bodies and health.