For decades, headlines about human evolution have chased superlatives: the oldest tool, the earliest art, the first evidence of complex behavior. While these discoveries drive research and grab attention, the quest for “firsts” reveals a fundamental truth about our understanding of prehistory: our timelines are provisional, and the record is incomplete.

The Problem with “Firsts”

Identifying the absolute earliest instance of a technology or behavior isn’t just about bragging rights; it’s critical for understanding why things happened in the sequence they did. For example, if rock art predates the extinction of Neanderthals, it raises the possibility that our extinct cousins also engaged in symbolic expression. But dating these discoveries is fraught with challenges.

The Case of Ancient Tools

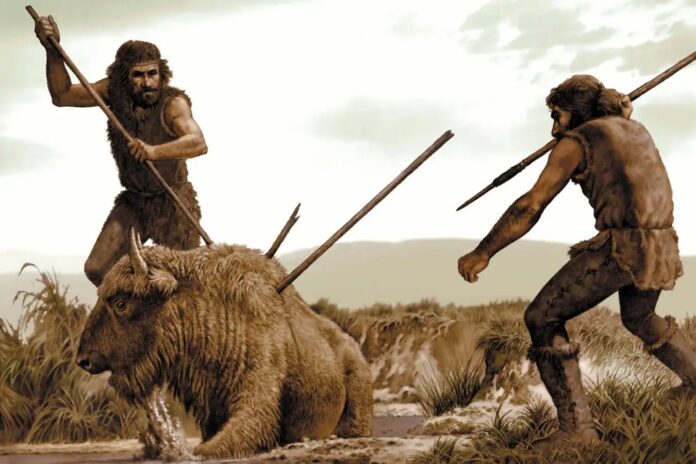

Recent finds in Greece have unearthed wooden tools dating back 430,000 years, making them the oldest known examples of their kind. However, this discovery doesn’t rewrite history entirely; it simply pushes back the known timeline. The Clacton Spear in the UK and wooden spears from Schöningen, Germany, have previously held this title, but dating uncertainties and revised analysis show that records are always subject to change.

The same applies to bone tools. While European sites like Boxgrove in the UK show evidence of bone hammers as early as 480,000 years ago, East Africa has yielded systematic bone toolmaking dating back 1.5 million years. These disparities emphasize that preservation biases our understanding: the African record is richer because of climate and geological conditions.

Composite Technologies: Poison Arrows and Hafted Tools

More recently, evidence from China reveals hafted stone tools (tools attached to handles) dating back 160,000 to 72,000 years ago. Similarly, the discovery of 60,000-year-old poison arrows in South Africa showcases early composite technology. These findings suggest that advanced techniques emerged gradually, not in sudden leaps. However, the scarcity of preserved evidence means older instances likely exist, undiscovered.

The Unreliable Record of Art

The dating of prehistoric art is particularly challenging. Cave paintings are difficult to date accurately, especially those older than 50,000 years, where carbon dating becomes ineffective. A hand stencil in Indonesia, dated to at least 67,800 years ago, is currently the oldest known rock art, but this “minimum age” leaves room for speculation: the artwork could be far older.

Why Some Records Are Better Than Others

Paleontologists rely on volume to build reliable timelines. Just as a large sample of marine mollusk fossils allows for detailed evolutionary tracking, extensive stone tool records provide a stronger foundation than rare finds like wooden artifacts. Early hominins like Orrorin and Ardipithecus spent much of their time in trees, making it unlikely they engaged in complex toolmaking.

The Future of Prehistory

Our understanding of human evolution remains provisional. Improved dating techniques and new archaeological discoveries will refine our timelines, but some uncertainties may persist. Just as the extinction of the dinosaurs is firmly established by the fossil record, the human story will continue to evolve as we uncover new evidence. We must acknowledge that some questions may never be answered definitively, and embrace the dynamic nature of prehistory.

Ultimately, the search for “firsts” is valuable, but we must interpret these findings with caution, recognizing that our understanding of the past is always subject to revision.