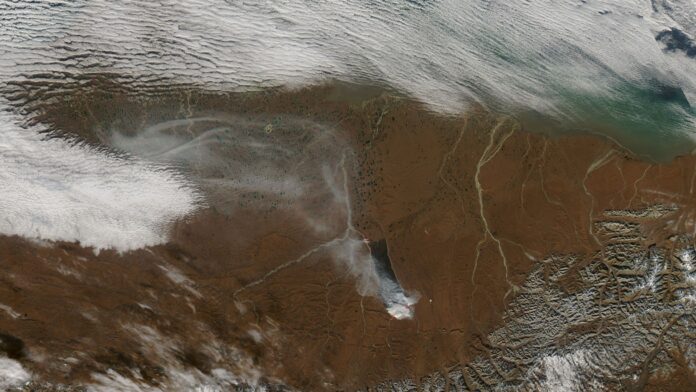

Wildfires in northern Alaska are now more frequent and severe than at any point in the last 3,000 years, according to new research published in Biogeosciences. This isn’t merely a recent uptick; it represents a fundamental shift in the region’s fire regime, driven by climate change and a rapid transformation of the Arctic landscape.

The Changing Arctic Fuel Load

For millennia, northern Alaska’s tundra was dominated by sedges and mosses—vegetation that doesn’t easily burn. However, rising temperatures are causing permafrost to thaw and shrubs to spread across the landscape, a process known as “shrubification.” These woody plants provide far more flammable fuel, dramatically increasing the risk of wildfires. This is not just about warmer temperatures: it’s about an ecosystem restructuring itself to burn more readily.

Researchers analyzed soil cores from nine peatlands between the Brooks Range and the Arctic Ocean, dating back 3,000 years. These cores revealed a sharp increase in charcoal deposits beginning in the mid-20th century, exceeding any previous wildfire activity. Combined with satellite data from 1969 to 2023, the study paints a clear picture: current wildfires are unlike anything seen in this region for three millennia.

Why This Matters: Beyond Alaska

The findings aren’t just about Alaska. The North Slope serves as a bellwether for Arctic tundra ecosystems worldwide. As warming continues, the same dynamics—permafrost thaw, shrub expansion, and increased lightning strikes—are likely to unfold across the Arctic, leading to more frequent and intense wildfires.

The research also suggests a disturbing trend: some recent fires are burning so hot (above 930°F) that they leave behind only ash, not charcoal. This means that current fire records may underestimate the true severity of recent blazes, as extreme heat destroys evidence of past burns.

The Feedback Loop

The increase in wildfires is a self-reinforcing cycle. As permafrost thaws, it drains surface water, favoring shrub growth over moisture-dependent sedges and mosses. More shrubs mean more fuel, leading to more fires, which further accelerate permafrost thaw and vegetation changes.

As lead author Angelica Feurdean explains, “If you have higher temperatures, you have higher shrub cover, more flammable biomass, and then more fires.” This creates a dangerous feedback loop that could reshape the Arctic landscape in decades to come.

The current wildfire activity in northern Alaska is not just a consequence of climate change; it is a harbinger of more severe changes to come. The Arctic is warming at twice the rate of the global average, and these findings demonstrate that the region is reaching a tipping point where wildfires are no longer an occasional event but a dominant force shaping the ecosystem.